Getting Naked

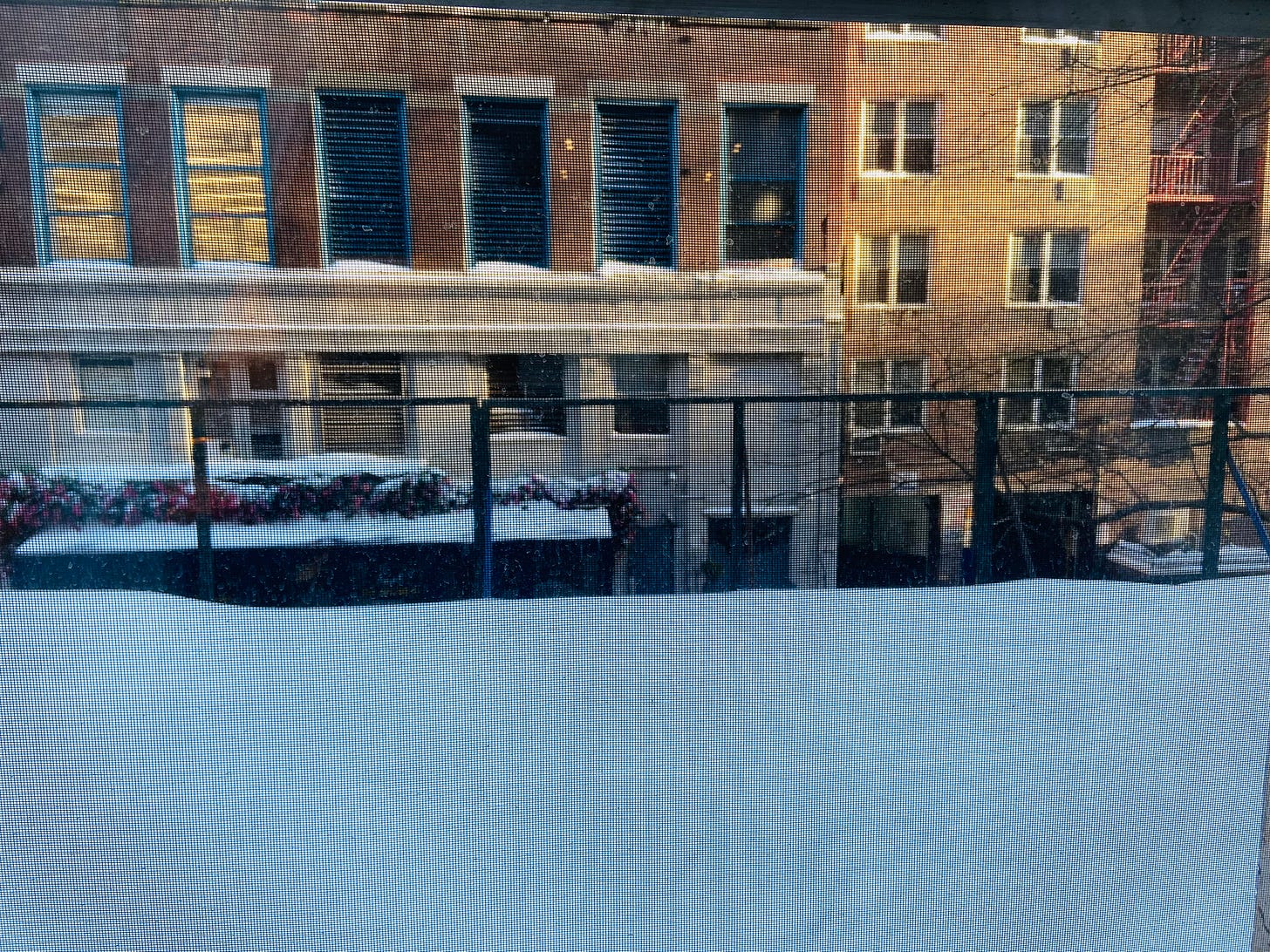

My apartment's exterior is a giant Glamour Don't.

My husband comes rushing in, the way he does when he can’t wait to tell me something. He jerks his head toward the window.

“It’s coming down in about a week,” he says.

“The whole…the scaffolding? Like, all of it?”

My question has taken some air out of his headline, but he’s still excited as he clarifies - the foreman said the metal bars and ladder that are directly in front of our living room window are coming down.

“We’ll still have the platform ‘til spring,” Philip continues – a reporter, breaking a story – “But the rest? Gone.”

“The gauze too?”

“Yup. All of it.” He waves his arm toward the mess outside our window like Leonard Bernstein dismissing an orchestra.

I give a little shriek and take my place at the far end of the window seat.

I spend a lot of time here, especially in the morning when no one’s awake. Here, I lean against throw pillows like a pasha, write, text, and read as much of the paper as I can bear. Reveling in the luxury of morning solitude, I stare mindlessly out the window. I watch neighbors nod to fellow, half-awake-dog-walkers at 6AM. I know the sound of the bread truck that pulls in front of the restaurant across the street and the three bangs on the door that follow it. When the kitchen crew hasn’t arrived yet, the driver leaves a brown paper bag of baguettes against the front door – an old-fashioned act of trust in a cynical world. I sense the quiet determination of porters and doormen who hose sidewalks like there’s a prize for the biggest puddle.

Or at least that’s what old me did. Current me sees nothing because I’m caged in by scaffolding and draped in gauze. I remember the day the latter appeared, white and snowy as the veil of a bride. Now, it’s grey and torn – the product of an ill-fated wedding that’s lasted way too long. Hey, Macarena, make this damned thing end.

It wasn’t supposed to be up for this long. But in New York, scaffolding months are like dog years. Complaining about it unites us neighbors as we wait for the elevator and collect our mail. I talk a big game about how much I hate it, but my dirty secret is that I don’t hate the dirty gauze.

When the bridge first appeared, I said “Let’s pretend it’s a balcony” to Philip, who, like the rest of the building, was in no mood for whimsy.

“Yeah, a balcony you can’t use because it’s covered with wheelbarrows and bricks and…what the hell is that?” he said, as a huge bucket of sludge was plopped directly in front of our window.

I sighed. I was glad the gauze was white and not black, diffusing light instead of blocking it. And I actually found it a kind of pretty - like a sheet of velum, making the world a little softer.

When I said so to Philip, he looked at me like I’d gone mad and he wasn’t exactly wrong.

But I wasn’t exactly me.

My mother had just been put into hospice and with it, my world into limbo. At first, we were told it would be a matter of days, maybe weeks. Weeks became months and my siblings and I became a network, connected by daily texts.

How was she today?

She ate a little quiche and slept.

The music therapist came, so she was happy.

She had her lungs drained. Bad, at first, now better. Sleeping.

We watched youtube videos.

She was agitated. Hospice nurse will check her meds.

We colored. She slept. A good day.

The texts, like strands of fishing wire, tethered us to her and to each other. They were mundane in their sameness, except when they weren’t.

She cried and yelled that she wants to die.

Texts like that made me stop breathing. Until hospice, I could count on one hand how many times I’d seen my mother cry. Her tears were dignified and contained - a tissue-dab to the corner of each eye, her sad smile, a promise that things would be okay. And she made them okay, even after my father died, when we pretended to be taking care of her while she took care of us.

Now, the discipline she’d maintained for 93 years was gone. Her tears were unrestrained, running wild, like fourth-graders set free on a playground.

We all acted differently then. Sometimes I thought it was the very word that did it to us - hospice. The final act. Permission to skip meetings and showers, to eat a handful of Wheat Thins and a scoop of vanilla ice cream and call it dinner. Hospice - the sickness that doesn’t come with Get Well cards. A terrifying, liberating admission that you’re waiting for death.

“The new normal,” became a phrase we applied to everything - from her pain, to the presence of full-time caregivers, to our exhaustion. The calls at sundown - when she yelled into the phone in a fearful, screechy tone that bore no resemblance to the soft one we’d known all our lives - were harder to get used to. But we came to expect and understand them too.

“This is just a side effect of the medication, and it happens at the end of the day,” I’d say into the phone, willing my voice to sound calming and certain, as I assured her that no one was trying to break into her house. I’d ask her to take deep breaths with me, and then, when she quieted, I’d sing “Que Sera Sera” until she joined me on the“whatever-will-be-will-be’s.” Sometimes, she’d say “Again,” and we’d start over.

I took New Jersey Transit a few days a week, working on the train and when she napped. Life became a long, drawn out, gauze-covered slog. Days blended together - a blur of sadness and stillness, like one long sick day – the kind you say you hate, but quietly embrace. I clung to it, because when this sick day ended, so would my life as a daughter. And I loved being a daughter. I loved being her daughter.

It often seemed like she was about to die. And then she didn’t. Sometimes the hospice nurse would say she was “winding down.” But a day later, she’d start eating again and we’d talk about what good color she had.

It was a year enveloped by a cloud of sameness. A year of spooning soup into a mouth that had lost its stiff upper lip, angling the spoon so chicken broth wouldn’t drip down her chin. A year of kissing her forehead and whispering “just a little more,” when she fell asleep between spoonfuls.

But also, a year of wishing for the thing I’d dreaded all my life. A year of wishing my mother would die. Which flooded me with guilt, because while most of that wish was for the end of her pain, some of it was for the end of mine.

It wasn’t only sad, it was tedious. The train rides. The sitting. The racking of the brain to think of stories to divert her and occasionally make her laugh. The endless tasks.

A phone call from Kecia, her caregiver, came on a Friday afternoon, at the end of a long week, when I was about to snap my laptop shut. With a sigh, I wondered what I needed to order from InstaCart.

“She’s fading,” Kecia said and I was calm, because she was said to be “fading” all the time. It was when she added, “The hospice nurse wants to talk to you,” that my eyes widened.

Arthur, who’d been seeing my mother for the past six months, had a quietness to his voice that stiffened my spine. He said “It looks like Florence is starting to shut down,” as if she were a shoe factory. But his voice was kind. If I wanted to see her, he said, it would be best to come soon.

And so I did.

Arthur said he thought she’d probably last the night. He said to talk to her because she might still be able to hear.

“She’ll go out nicely,” he said, “I can tell.” I nodded proudly. Of course she would. He said we were in good hands with Kecia and that I should call if we needed him. I wanted him to stay, and I wanted him to go. I had no idea what I wanted.

My memories of the night are both sharp and hazy. I held her hand, sometimes letting go for a few minutes, then quickly grabbing it back. I sang Que Sera Sera, and she made a soft sound that I wanted to think was singing.

“Hey, F, I can’t tell if you’re singing or moaning,” I said to her unmoving face.

I leaned closer and angled my head, trying to peer under the lashes of her closed eyes. I stayed that way, willing her to laugh at her bad singing and say “so what else is new?” Silently, I begged her to open her eyes and smile her gracious smile. To stay and be my mother. My F.

By morning, her slow pulse became no pulse.

Kecia’s eyes were steady and kind as she whispered, “she’s gone.” I stared at her dumbly.

She put a rolled-up towel under my mother’s chin so her mouth wouldn’t hang open – “She’s too pretty for that” – and told me to hurry and open the front door so her spirit could escape.

I’ll forget a lot of things, but I’ll never forget the feel of Kecia’s strong hand on the small of my back at the moment I needed it most.

My brother, sister and I held hands and did all the things you do – a funeral, a shiva, a hazy year of mourning.

And then, just as people said it would, after the first year, the haze lifted. The dull constant ache was gone. But in its place were sharper stabs of pain - the ones that came when I’d think, “I better call F to remind her it’s Daylight Savings.” Or when a plane landed in a new city and I started to tap her number into my phone. Or when my eyes lit on a bunch of pale pink tulips at the deli.

Those are the pains that remain - sharp, stabbing, intermittent. They come without warning. Sometimes they’re gone in an instant. Sometimes, I can’t shake them for days.

I sit in the window seat, pecking these words out, catching a glimpse, through the curtain, of a workman’s orange sweatshirt and camouflage pants.

“Oh my God, they’re doing it - they’re taking it down!” I yell to Philip.

We throw the curtains open and watch, because we can’t get over how beautiful it is. I meet the eyes of one of the men and smile. He smiles back.

When I look out again, the metal staircase that has blocked our view is gone. As are the wooden planks and the bricks. The bridge (our balcony) is still there for now, and our view is hardly clear. But it’s better.

The dirty, foggy, shredded twisted, gauze is gone.

So long, old friend.

You’ve shielded me well.

But it’s time to get on with it.

After all, whatever will be will be.

This took my breath away and made me cry. It’s exactly 2 years today that she left us and it leaves a hole in my heart. It was such a journey and a heartfelt long goodbye taking care of our dear beautiful mother. Thank you for writing this. ❤️❤️

This is so human and so beautiful.