Room 1517

Jesus, justice and me.

The woman behind me is suffering more than anyone has ever suffered in the history of jury duty.

She, and the woman at the front desk are engaged in a game of verbal ping-pong. The woman at the front desk over-explains. The one behind me over-reacts. The front desk woman wears a striped sweater. The woman behind me is blonde.

“Listen up,” bellows Stripes.

“Jesus Christ” mutters The Blonde.

“When you fill out the form that was given to you upon arrival, do not use check marks, and do not use x’s. They can’t be read by the computer.”

The Blonde lets out a majorly pissed off sigh.

“You need to fill in the circle. The entire circle. Do not put a little dot in the middle, because the computer can not read a little dot. It can only read a fully filled-in circle.”

The Blonde responds by summoning Jesus Christ again, and rapidly tapping her nails.

I can’t tell if Stripes loves or hates having to explain the art of circle-filling-in. Her tone and body language imply annoyance at having to give this kind of direction. And yet. She clearly likes reminding us that, as a group, we’re kind of dumb:

“I can promise you that no matter how many times I say this, at least one person will come up here with a check mark or an X in the circles,” she says, shaking her head sadly, then adds “at least one,” for emphasis.

The Blonde sighs so loudly, I can practically feel the heat of her exasperation on my neck.

“And when you fill in the dates,” Stripes continues, “fill in each circle. If the date is 10/7/25, you circle one number in each column and then, on top of that column, you write the corresponding number. Today’s date on top, corresponding numbers in the circles below. Again. Someone will come up here without having done that.”

“For fuck’s sake,” says The Blonde and I get her point. This is the second time we’ve been given this particular direction. Just how idiotic does Stripes think we are? She directs those whose names start with A though F to bring their forms up. The woman to my right glances at my form and leans over.

“I think she said you’re supposed to put the date at the top,” she whispers.

Oh my God. I’m the idiot. I thank my neighbor for saving me from being “at least one person” and scribble the date where I was told (twice) to put it.

Once the forms are handed in, we settle into our respective grooves. Laptops and books are cracked open. Phones blink with text messages. New friends converse (which is annoying to the rest of us.)

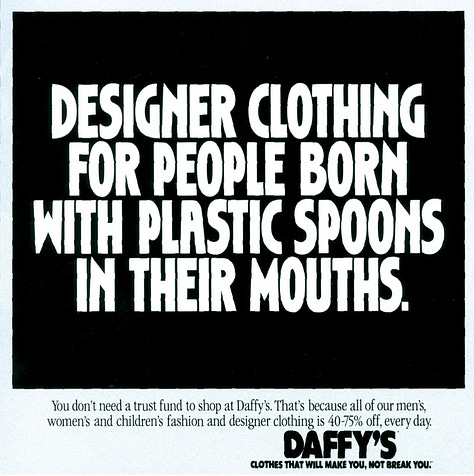

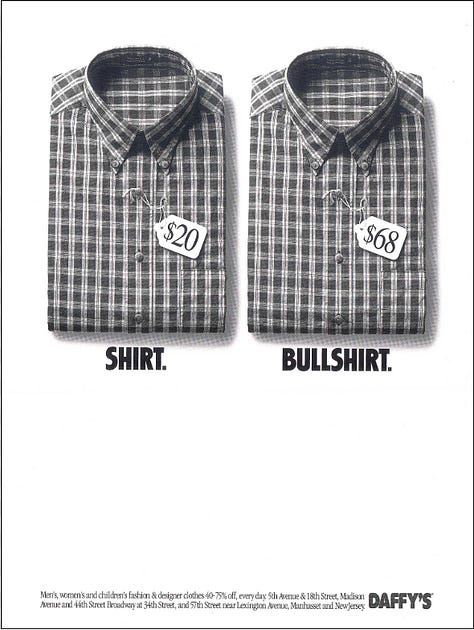

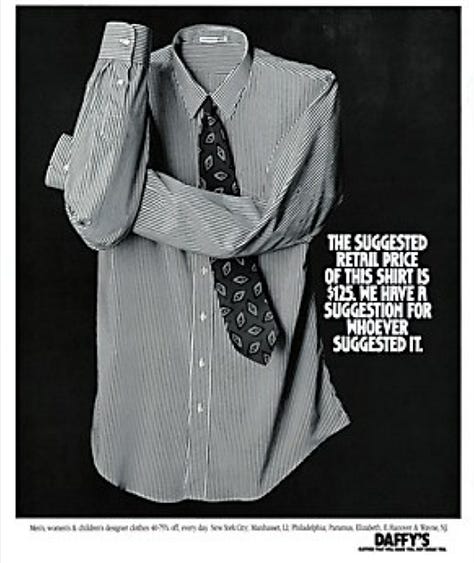

I settle in, glad I wore a simple black t-shirt and high-waisted pants. I feel like I look put-together and appropriate. I think back to the first time I had jury duty, when I was barely 30 and very single. I wore a Norma Kamali charcoal-grey boucle mini-dress that I’d gotten at Daffy’s. Its straps slipped from my shoulders, which I did little to address (someone had once told me I looked like Jennifer Beals from Flashdance, a compliment I’d taken way too seriously.) The falling straps revealed a scoop-necked, black stretchy top that I wore with the dress. I cringe as I write this, not because it sounds so bad, but because it was. Or at least, inappropriate as attire in which to sit before judges, lawyers, defendants, and pretty much anyone but a guy I was flirting with at an East Village Bar.

I sink into my seat. My book is delicious.

“Okay,” says Stripes into the mic, then pauses for dramatic effect.

Like thunder after lightning, the Blonde does her part.

“Jesus,” she hisses, rummaging through her bag for what I hope isn’t a weapon.

“I’m going to call 60 names.” Stripes pauses to let it sink in. “When I call your name, say ‘here,’ or whatever word you’d like, and then line up to my right.”

I sink down further, to keep from being called, but Stripes doesn’t seem to read my body language.

“Debra Fried,” she says, sounding annoyed with me for getting chosen first.

I yell “here” and tuck my book into my tote. Others are called and a messy line begins to form to the right of Stripes. One guy responds to his name by yelling “honk honk.” Some people laugh. The Blonde groans like she’s been hit with sciatica.

Somehow, despite being called first, I end up at the back of the line, and a guard ushers all 60 of us down to the 13th floor. We take our seats in the courtroom and it’s a shock to see the defendant sitting at a table. He wears an untucked, white button-down shirt that’s a bit too large. It’s creased, as if just taken out of the package. It seems intrusive that we should get to see him before we’re on the case, but there he is, looking way more relaxed than I would if my destiny were in the hands of a roomful of strangers.

The judge asks us to stand, raise our right hands, and asks if we promise to be fair and truthful. People murmur “yes” and a man to my left says “I promise” with a touching level of sincerity. There’s something sweet and pure about a roomful of people making a promise together and I’m embarrassed at how moved I feel.

My eye is caught by a flicker of movement. The defendant is leaning in, whispering to his lawyer, and laughing. The lawyer lifts her chin toward those of us with our hands in the air and the defendant’s laughter stops.

As the judge explains the rules of engagement, I’m reminded of my first time at jury duty. I was moved by the sincerity of my fellow jurors then too - and surprised by my own earnestness. Deciding the fate of another person - whether he’d go to jail or go free - was not something we took lightly. I remember welling up when it was over, feeling that I understood, for the first time, what it was to be American.

The judge asks each of the people at the tables before him to stand as they’re introduced. It’s like the beginning of a panel discussion, but we don’t applaud. First, each lawyer stands, looking solemn and nodding respectfully at us potential jurors. And then the defendant rises. I’m struck by how vulnerable he must feel. Standing there. Hoping a roomful of strangers will be just.

“You’re going to hear a lot about what this man is accused of doing,” the judge says, “but it’s your job not to judge him until you’ve heard all the evidence and can do so fairly.” He asks us to ask ourselves if we can do this.

I nod, realizing, to my annoyance, that I’m becoming invested. I’d thought I might use an upcoming freelance gig to get out of serving, but dammit, I’m all in. Once a believer, always a believer.

The judge clears his throat and begins. The defendant, he explains, is accused of approaching a woman near a wooded area of Central Park. A hush comes over the room as our collective fidgeting ceases. People lean in. I sit up straighter.

He continues explaining the accusation, according to which, the man’s pants were open and he held his penis in his hand. I’m childishly taken aback by the word “penis,” then feel amused at myself for reacting like a 4th-grader. I almost smile, but I’m shaken by what is being said. “He is accused of pushing himself against the woman, who was able to get away,” the judge says.

The defendant sits calmly, the cuffs of his too-big shirt partially covering his hands. I search his face for tells. I want to think I’m assessing him in a fair manner, but I realize that I’m squinting angrily.

I think he did it. And I hate him.

I shake my head, wanting to snap myself out of it, but I can’t.

The judge talks about the importance of hearing the facts, and I feel awful because I don’t think I can be fair to this man. I’ve pre-judged him and it’s partly because he laughed when we had our hands in the air.

But it’s also because I can picture all too clearly what the judge described.

“Those of you who serve will hear a lot more in the coming days, but for now, I need you to ask yourself, based on what you’ve heard so far, if you’ll be able to be impartial. If the answer is no, please be prepared to state your reason.”

We shuffle to the hallway, much more quiet than we were on our way in. The line of those who don’t feel they can be impartial is long and I hate being on it. I want to go stand with the fair people.

When it’s my turn to go in, I’m surprised yet again. I’d pictured myself walking up to the judge - “approaching the bench” in a dramatic fashion, but I’m not invited to do so. I stand near the defendant’s table, far enough from the judge to have to speak loudly.

When I’m asked to say my name, there’s a catch in my voice.

“Why is it you feel you can’t be impartial?” the judge asks.

“I was… I was the victim of something similar to what you described,” I say and he nods as if he knew that would be my answer.

“I’m sorry that happened and that you had to talk about it here,” the judge says. My “thank you” comes out as a whisper. I return to the hallway, noting that The Partials are almost all female. Of course we are.

I remember being on a subway platform when I first lived in New York. I stood at the front, to get onto the first car. My eyes met those of the only other person standing there - a man who smiled at me. Reflexively, I smiled back. He looked down at himself. His pants were open. I gasped. He raised his head and met my eyes again, but this time, his smile had become a menacing laugh. It lasted all of ten seconds. And all of 40 years. I can still feel my shock and my humiliation. And later, my anger at having felt that way - after all, it was him whose body was exposed. Him who was living the ultimate embarrassment-dream of being flaccidly half-naked in public. And yet there I stood - fully clothed and totally threatened.

So much power in that moment. None of it mine.

That experience was mild compared to what it could have been. But it makes me angrier now. My daughter is the age I was then.

It was the laugh that went through me. I think of other laughs, from other men. Taunting laughs. Mean laughs. The defendant’s laugh wasn’t mean - it was casual. But I can’t deny that it made me dislike him.

My feeling isn’t fair and I don’t belong in this trial because, obviously, the man in the white shirt deserves impartiality.

Those of us who’ve been dismissed are walked back to Room 1517, like schoolchildren returning from recess. But we’re not in high spirits. I sink into my seat.

The Blonde is ripping through a magazine like she wants to kill it.

I open my book, but don’t read it.

We’re dismissed at the end of the day and told we don’t have to do jury duty for four years. A few people clap, but I don’t feel jubilant. I feel like I failed.

Amongst the people on the elevator is a woman who’d been in the Partial line.

“What did you say when they asked your reason?” she says.

I smile awkwardly because the elevator is full.

“I, um…” I say.

“Yeah, same here,” she answers. “All of us, I guess.”

I don’t answer and we’re silent until we get to the lobby.

As I head up Centre Street, I remember walking home the first time I was here, in my black tights and grey mini - inappropriately sexy, yet touchingly innocent. Innocent enough to believe in our justice system with all my heart. Innocent enough to be clear-eyed and honest. Innocent enough to be fair.

I miss that girl.

I miss the country we were then.

Where I believed that fairness was not only a goal, but a given.

Where people were put on trial before being convicted.

I pass Canal Street, where fake Louis Vuitton handbags are laid out on blankets - a pocketbook picnic. A few weeks from now, the guys selling them will be rounded up by ICE.

I continue walking uptown.

I’m uneasy and ashamed.

I’m glad I’m headed home because I need the safety I feel there.

Lately, I don’t recognize my country.

And today, I don’t recognize myself.

.

Thank you for being brave enough to write this. You are an unexpected source of inspiration for me right now.

Such a familiar feeling. You continue to amaze me in the way you can so intimately describe such universal experience. Bless you for making me feel human today.